A Leica Pilgrimage

We had dinner in Wetzlar on the first night, Elle and I, at a cute little restaurant with a lot of doilies everywhere. We sat in a mezzanine of sorts, looking down from our little table on the other diners below, and their sumptuous-looking plates, wondering what everyone was eating and saying. When we told the waiter we were visiting from Chicago, he told us that he “made my honey-days” in Salt Lake City, with a stop in Vegas for good measure. This visit was not a honeymoon for us, but it was special nonetheless: it was our first adventure in Europe together, and my first visit to Wetzlar. I had long imagined standing in front of the Binding am Eisenmarkt, where Oskar Barnack took one of the first images with the kleine film kamera. I fantasized that I’d easily find all the places I’d seen in Gianni Rogliatti’s Leica - The First Sixty Years and in Günter Osterloh’s Leica M, both of which I’d read and re-read, time and again. Simply upon arriving in the promised land of Wetzlar, I figured, I’d automatically find – illuminated for my lens – the corn market where Barnack made some of the first Ur-Leica photos, the flooded street filled with life-jacketed passengers in canoes, a German officer using a periscope, a poor man with bushy white mustache and ragged cloak, and maybe even a distinguished gentleman sitting on the very park bench where Dr. Ernst Leitz II sat when Barnack took his picture.

A journey back to the land where it all began: my One Hundred Years of the Leica Camera Pilgrimage.

We wandered back to the hotel after dark, window-shopping the urban and pastoral stores alike. It was our first night on vacation in Europe, and we were jetlagged and confused and stumbling over the cobblestones after a couple of glasses of wine. All of these incredibly old frame buildings all look the same, I thought, I wonder of I’ll have to ask someone tomorrow where Eisenmarkt is, or if it’s on the map.

We rounded a corner and ambled down the cobblestones. I think I went ahead of Elle a bit, and was probably fussing with my camera when I looked down and found myself standing on a shiny new manhole cover imprinted with an Ur-Leica. I blinked slowly, looking again in disbelief at the Ur-Leica underneath my feet. I thought, Yep, that’s an Ur-Leica, all right. And what’s it doing here? On the ground? Under my feet? I shuffled back a step quickly, and rubbed my eyes. I looked up: This is not the place.

“Hey Elle – look at this: ‘First Leica Picture was taken here, 1914, by the inventor and visionary Oskar Barnack’.”

No kidding, I thought, looking up, Interesting… I scratched my head, then looked back over my shoulder.

There it was. Almost the exact visage Barnack had photographed one hundred years ago. Wheeling around, I started taking pictures like it was a race – overjoyed to have found the Eisenmarkt.

The next day we loaded up with color film and Monochrom batteries (well, me, mainly), and headed out to explore Wetzlar. We wandered about, fascinated by the architecture and the antiquity of the old town, and lingered on the Old Lahn Bridge, one of the oldest in Germany, built around 1250 or so. We ducked into shops and bought a few little things here and there. We read placards and took pictures of nearly everything we saw. Well, I did anyhow – Elle indulged me as I delighted around Wetzlar, explaining the significance of this and that, at every turn.

We came across exactly the kind of bookstore we love to browse, with a bunch of Leica books and literature in the window. Closed for holiday. We took a picture anyway.

Already I had started to think of this trip as a sort of Leica pilgrimage. More than just a stop along our travels, I pay homage to Oskar Barnack and Leica by coming to Wetzlar this year. But it was a vacation, too, and Elle and I looked forward to getting to Cologne where we’d shop and eat and drink Kölsch and meet up with Fred and Simon (two friends from Chicago and Aberdeen), and take photos and enjoy ourselves in this inspiring, cobblestoned place. After all, we’re city kids on summer vacation in Germany. And why not? It’s like a honey-day.

At another bookstore I asked for anything about Leica, and the proprietor showed me a few books in German. His English was flawless, and he said, “No one in Wetzlar carries a camera, no one cares much about it here.” I took a picture.

In the afternoon, we met Mr. & Mrs. Helmut Fennel, a member of Leica Historica, who gave us an excellent tour of the town. At the Wetzlar Dom (cathedral), Mr. Fennel explained that Ernst Leitz himself had donated the beautiful pipe organ there, under the strict stipulation that the church clergy hear confessions from both Catholics and Protestants. This resonated with me, and reminded me of the Leitz family’s perilous and compassionate task of spiriting out of the country many members of Wetzlar’s Jewish community during the Second World War; the kindness of the Leitz family made this journey feel that much more like a pilgrimage.

As we walked and talked, Mr. Fennel told me that Lars Netopil’s Classic Cameras shop was just around the corner from the Wetzlar Dom (a fact I had missed – it seems to have been the only corner we hadn’t already turned). I was thrilled at the prospect of meeting another Leicaphile, and especially one with a shop! After all, I thought, this is a vacation, and shopping is part of a vacation. Then I thought: Wait – is there shopping on pilgrimages? What if there’s no shopping on pilgrimages, and there’s a black paint button-rewind M2!

Then, as we sauntered around the corner we found the store shuttered.

I almost cried, right there in the street.

I took a picture.

Mr. Fennel told us this story: Ernst Leitz II was traveling when he bumped into a gentleman from his company with whom he was friendly. After a moment in conversation, the man said, “Ernst, perhaps you need some new clothes to travel in – I’m surprised to see the state of your jacket and cuffs. Your tie wants pressing, too.”

“What does it matter?” Leitz said, taking no offense, “There is no one to impress, no one knows me here.”

Some weeks later the man encountered Leitz walking nearby his home in Wetzlar, and he said, “Ernst, I do think you need to see my tailor; certainly a man of your stature can stand to have a new jacket and shirt, and perhaps a fine pair of trousers, too.”

Ernst Leitz replied, “What does it matter? There is no one to impress, everyone knows me here.”

We walked to the “old” Leitz factory, which now houses the Microscopy Division. Nearby there is a small, tidy, flower-filled garden with a headstone-type marker for Oskar Barnack. Needless to say, I took a picture. We walked up a steep hill to the Leitz Mansion, a grand affair with porticoes and thick columns and beautifully manicured grounds. The mansion now houses flats, and we joked about how grand they must be, and shouldn’t we all take a flat together here next summer? The view was likewise grand, and we stood for a while admiring it and the white mansion on the hill behind us.

After fond farewells, Elle and I walked over to Eisenmarkt to make a few photos, but the streets were empty. We had too much exploring to do to wait for the perfect light and the right passerby to arrive in my viewfinder, so I made a few photos and we set about looking for more adventure.

We met a man with a four-foot-tall red plastic statue of Goethe under his arm. The light was fabulous. He met us with a warm smile and (correctly guessing we were tourists) pointed up to a stately old building saying, “This is where Goethe wrote The Sorrows of Young Werther. It made him famous. 1774. He was up in the garret, there. He drank eight bottles of wine a day.”

I took a picture.

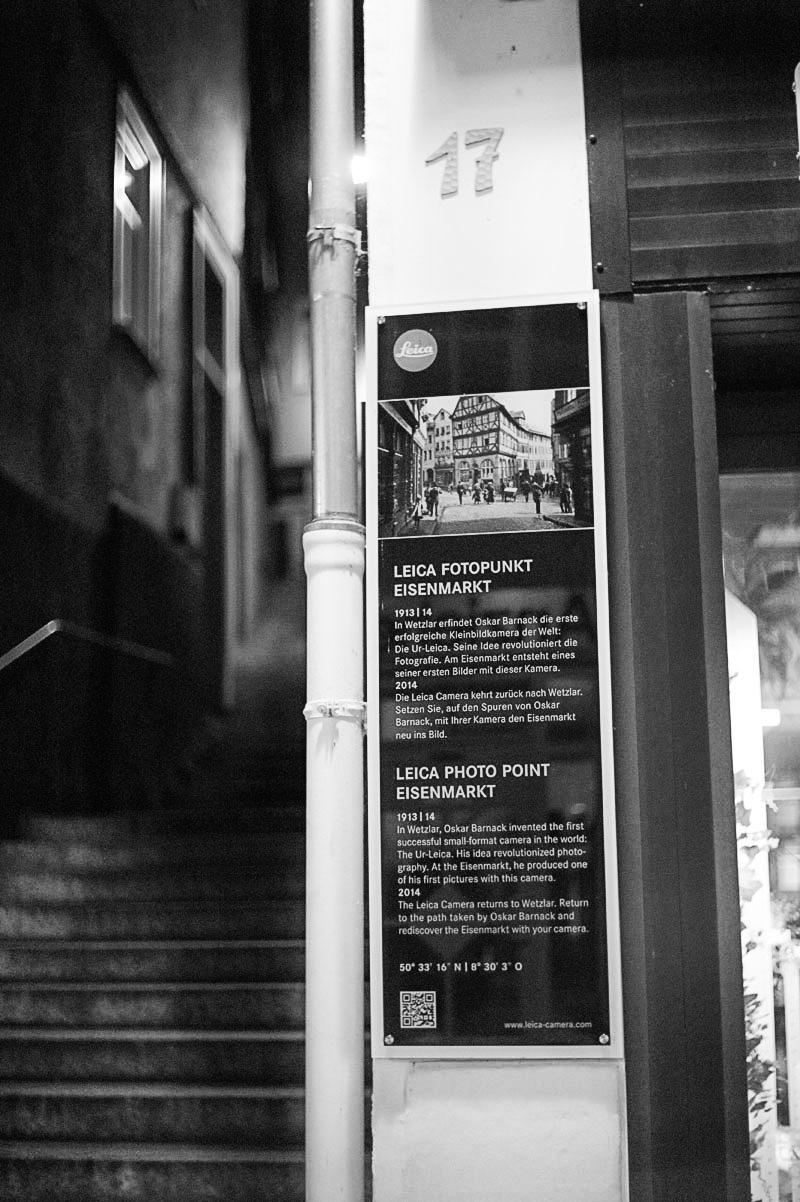

As evening approached, I ran into an amiable fellow from Hong Kong. It was the silver M camera he carried that tipped me off. He stood there at Eisenmarkt, looking down also, and found himself standing on a shiny new manhole cover imprinted with an Ur-Leica, wondering, Yep, that’s an Ur-Leica, all right. And what is it doing here, on the ground, under my feet?

We chatted for a few minutes and looked at the placard there and read it together. The coordinates are listed at the bottom of the placard:

50° 33’ 16” N | 8° 30’ 3” O

“How about the news at Photokina?”

“What about a 28 Summilux?!”

“And the fabled new Monochrom camera…?”

Ah, the woes of the Leicaphile! Realizing that we could stand there all night schmoozing (and that our better halves were waiting for us), we shook hands, exchanged cards and bid each other farewell and happy shooting.

We made our way to a café in the middle of Eisenmarkt with a sign that read Husband’s Day Care Center. We sat for a while, until dusk, talking and joking and sampling the local wine and pilsner.

We lingered again on the Old Lahn Bridge at sunset, and saw in the distance a man fishing in the center of the shallow Lahn River. There’s a lighted fountain near the bridge, and we spied a little wine garden beyond it. We found spectacular reflections on the water underneath the bridge – shadows against the stones, set by an unknown mason more than seven hundred years ago. We took a picture.

Elle had a glass of excellent Rhine wine and I had a nibble of some fiery grape spirit. We sat and talked there by the Lahn, listening to crickets and the chatter in German around us; every now and then a peal of wild laughter from the beer garden across the river. We swatted mosquitos and sipped our drinks. The fountain and lights sprung up every now and then and we watched, rapt. Content.

We sat there long enough that the laughter across the river called to us, I suppose. We walked back across the bridge, where the howls from the beer garden engulfed us as we approached. We took an empty table by the water, drank from steins and ate like drunken lords – laughing aloud the whole time. It’s infectious in a beer garden, I think.

The next day, continuing my pilgrimage, I went to worship at the newly consecrated temple, Leitz Park. After a coffee in the fresh, whitewashed sunlight of the Café Leitz, I made my way across the promenade into the stunning gallery and reception area in the main building. Surely, the front desk staff had seen a lot of excited Leica-tourists, but none as excited as I describing my pilgrimage. They nodded serenely.

“Feel free to look around,” they bade me.

On display was a replica of the Ur-Leica, a Model A, a number of microscopy relics and other holy Leica icons, and Barnack’s movie cameras. I stood before each, mouth agape. This truly was the Leica holy land, a new Bethlehem – all that’s missing are Barnack’s own vestments. And to top it all off, Leitz Park has the best museum gift shop ever: a Leica Store.

There truly is shopping on pilgrimages, I decided. So I poked around the t-shirts and sport optics and whatnot, and then decided to find the Ur-Leica.

I snuck up behind a group on a tour and clung to their heels. We piled into a dark hallway with walls painted black and little Leica dioramas – small displays built into the wall behind heavy glass, exquisitely lit – of electronic camera innards, optical achievements and parts, and other curios of the science of Leica.

I asked the docent if I could hold the Ur-Leica and was met with an amused grin.

The hallway opens into a sparsely lit room with a long display of black boxes and pedestals arranged in a manner that seems haphazard at first: an array of nearly every camera and lens ever put into production, each displayed atop a little black cylinder. A Luxus, and a IIId, and an Elmax and an Anastigmat – it was a Leicaphile’s dream. I walked through the exhibit five times.

There are large, plate-glass windows looking into the actual manufacturing plant where lab-coated, hair-netted technicians turn dials on computers, and point up at monitor, conferring. At another station, a woman carefully paints lacquer onto the edges of lens elements with the help of a microscope and monitor. It was like the zoo, and I thought in the hushed whisper of a documentary narrator reporting surreptitiously from the brush: The elusive Leitz lens technician: rarely seen in the wild, subsists mainly on coffee and aspheres, with the occasional cigarette in the employee lounge, only breaking from his rigorous calibration labors every few hours…

I was excited to see the inner workings of Leica on display here, but it felt strangely voyeuristic. I waved to one technician (perhaps to cheer him up) and gave the thumbs up, hoisting my camera. He smiled and nodded and went back to work, adjusting a dial then the lens on the optic bench.

On the far wall at the end of the unlit hall was the large frosted “A La Carte” window, where you can make a date to arrive here and watch your custom-built camera being made. I wondered if the window rolls up or how it works, instinctively looking around for a coin slot for the peep show and fishing around for coins in my pocket.

The dark hall curves around, leading to more display boxes lining the walls at eye level: an Hermès camera, a Titanium M9 kit, the new Leica M-A set, and other tantalizing samples from the digital lineage.

I found myself drooling. I wiped my mouth on my sleeve, and took a picture.

After a while of wandering around aimlessly, I convinced myself that it was time to go. I waved goodbye to the gals at the front desk and walked out into the bright sunlight with a smile on my face. Proud to be associated with Leica – a company that pushes the limits of human technology with innovation, perseverance and finesse – I travel on, feeling more connected to both my family business and the Leica brand than ever before.

Next stop: Cologne and Photokina. I’ve got Elle, two train tickets, and my M7 – what else could anyone want? There’s nothing like great travel partners, and an adventure beckoning in front of you. And, there’s nothing like a Leica. But this I already knew before setting out on my pilgrimage.

Thank you, Oskar Barnack. And, congratulations, Leica.